Secrets of Ireland’s boglands

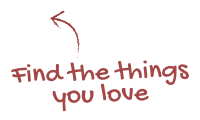

“Sometimes all you can hear are the insects on the breeze, and in spring when the call of the cuckoo echoes in the silence, it’s a magic place.”

That’s Colm Malone, a local park ranger at Clara Bog, County Offaly, summing up his work environment. It’s poetic, but then the tranquillity of the boglands, the beauty of this quiet landscape, would bring poetry to anyone’s heart.

A frosty morning on Clara Bog, County Offaly

Magic of the bogs

There is magic in these Hidden Heartlands, but the science is simple enough. A bog is a flat wetland that accumulates peat, or dead plant material, to a considerable depth below ground level. On the island of Ireland, many of them occur in the middle of the island, in an area known as Ireland's Hidden Heartlands, although mountain and coastal areas also have their share.

The boglands in counties such as Offaly and Longford are mainly raised bogs. Their construction is straightforward, though time-consuming: over thousands of years undecomposed plant material forms a thick and almost impenetrable layer of peat that progressively grows. The upper surface is then colonised by species such as moss, and the raised bog flourishes.

Round-leaved sundew © Tina Claffey

Now rare in Europe, these bogs are places of delicate splendour. In Ireland, various species of sphagnum moss thrive because they can survive on mineral-poor rainwater. Nicknamed the “builder of the bog”, sphagnum can absorb 20 times its own weight in water.

“Without sphagnum moss we’d have no bog. These beautiful plants frozen in time in the deep bog pools, also hold tiny worlds of fauna as well,” says photographer Tina Claffey. Tina specialises in nature photography around Ireland’s bogs and wetlands and has just published a book on the subject called Portal – Otherworldly Wonders of Ireland's Bogs, Wetlands & Eskers.

A living tapestry

“I’ve been fascinated with the living tapestry of the flora and fauna of our bogs and wetlands for years. This ancient wilderness on our doorstep is home to so many different plants and animals. And every season has its own beauty.

“One of my favourite flowers is the beautiful marsh marigold, one of the first flowers in springtime. It’s a godsend to the emerging spring insects,” Tina explains.

But should these insects desire a long life, they need to be wary of Ireland’s three insectivorous plants, the bladderwort, butterwort and the sundew.

Beauty and menace

Enticingly attractive in their vivid colours, they come with a warning – their sticky tentacles can be a matter of life or death for any passing mayfly, moth or other insect.

Beauty and menace blend seamlessly on the bog.

Life on the bog

L-R: Photographer Tina Claffey; birch shieldbug; marsh fritillary; devil's matchstick lichen © Tina Claffey

Legend and life on the bog

For centuries the boglands provided turf for domestic heating and cooking, as well as for commercial enterprises.

But the environmental cost of using turf in this way has become apparent over recent decades, and the practice is being phased out. Instead these serene places have become a collection of nature reserves where a very specific flora and fauna flourishes.

Distinctive habitats

Take your time and you might see a fox munching on bilberries, a kestrel stalking a field mouse, or dragonflies flitting about the wild orchids. The strange, ancient, magic boglands of Ireland are home to a cast of characters who intimately know every inch of their distinctive habitat.

The hares know all about the bogs, too – where to shelter, where to find the best hummocks to graze on, and how to escape predators. This they do with commendable élan. Although their feet look like a clown’s, a hare can speed across the bog with an acceleration that wouldn’t disgrace a Formula One racing driver. It is a startlingly dramatic sight.

A hare among the bog cotton © Fáilte Ireland/Tourism Ireland

The hare holds one other piece of information: the location of the entrance to the Otherworld, where the gods and heroes dwell.

Oddly enough, this happens to be in Ireland’s boglands, if legend is to be believed. According to the same source, hares also know where buried treasure lies; so they’re a multi-tasking, buck-teethed bargain.

Dancing lights

The decaying material of the bogland produces another phenomenon, called “will o’ the wisp”, or sometimes more graphically “the dreadful fairy lights” – and we’re not talking Christmas tree lights.

Will-o’-the-wisp is only seen in the darkest of nights, a light dancing on the bog away in the distance. These, it was widely accepted at one time, were spirits of the dead luring travellers into treacherous marshes.

Now trapped in the bogland, the spirits could not enter either heaven or hell, and spent their days wandering the earth.

Bram Stoker, author of Dracula © Alamy

The Count Dracula connection

The will-o’-the-wisp makes an appearance in Dracula. Author Bram Stoker, a Dublin man, never visited Transylvania, but he had travelled extensively through Ireland, and knew the boglands well.

His extravagantly-fanged Count refers to the common folk belief that these strange bog lights mark where treasure is buried. Count Dracula was always keen to help.

Scientific explanations

More pragmatic scientific explanations for will-o’-the-wisp generally focus on the spontaneous ignition of hydrocarbon gases emitted by the decaying peat.

The legends of course, come from the people who have lived round the boglands since pre-history – so they’ve had plenty of time to hone their folklore, their tall tales, and their sagas.

Old Croghan Man, Kingship and Sacrifice Exhibition © National Museum of Ireland

The sinister side of the bogs

Those who passed the folk tales from generation to generation have long had tangible evidence of something otherworldly about the bogs.

“Where every hill has its heroes / and every bog its bones,” wrote the Northern Ireland author Sam Hanna Bell and indeed bones are regularly uncovered from the peat. Many people have come to an untimely end: some perhaps trying to find their way home across the treacherous swamps in the dark, stumbled off the safe pathway.

Iron Age murder victims

Others have met their deaths in more spine-chilling fashion. In 2003, local police in County Offaly were contacted after a body was found in the bog near Croghan Hill.

The State Pathologist soon ascertained this was a historic case. Subsequent research revealed that the body belonged to a tall man in his twenties, who had suffered a very violent death – some time in the earlier part of Ireland’s Iron Age (800BC-400AD). He had been stabbed, beheaded, and his nipples cut off.

In County Meath in 2003 another Iron Age murder victim was found – he too appeared to have met an exceptionally gruesome end. These two men – along with many more found in the bogland – are referred to as the Bog Bodies or the Bog People.

Uncovering the Bog Bodies

Isabella Mulhall, assistant keeper in the Irish Antiquities Division and coordinator of the Bog Bodies Research Project at the National Museum of Ireland, explains the importance of these finds: “The preservative nature of the bogs has led to the existence of what are called the Bog Bodies or the Bog People – human remains which are oftimes remarkably well-preserved.

“With research,” she says, “it’s possible to work out how they died and indeed who they might have been....they have given us an opportunity to come face-to-face with our ancestors.”

National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin © Tourism Ireland

The Kingship and Sacrifice Exhibition at the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin investigates this phenomenon and displays the Bog Bodies, as well as other items including royal regalia, utensils and weapons. “The violence meted out to these individuals – and many of those found across western Europe – was excessive,” notes Isabella. “This was a traumatic end to their lives.

Ambassadors of their time

“Whatever the circumstances of their brutal and untimely demise. these remarkable individuals have come to us as ambassadors of their time, speaking across the millennia.

“They share with us not only the darker elements of their enigmatic worlds – of murder and of human sacrifice – but also the most elemental aspects of their everyday lives, aspects that we may all relate to in our shared humanity.”

Scenes from Ireland's bogs

L-R: Mongan Bog, County Offaly; bog rosemary, Clara Bog, County Offaly; Lough Boora Discovery Park, County Offaly; wildflower, Clara Bog, County Offaly

Discovering the bogland

Turf from the bog is part of the culture of Ireland. The smell of peat burning in rural parts for many centuries told a traveller they were home. Poets, artists and writers have been influenced by the bog, by its aromas, by its sounds, and by its silence.

Environmental impact

The environmental impact of burning turf is now understood, and conservation efforts have resulted in the practice being gradually phased out. The undisturbed boglands store vast quantities of carbon, so curtailing turf cutting has greatly aided measures designed to avert climate change.

This positive step has the bonus of preserving wild spaces in the hidden heartlands, creating a chain of nature reserves and havens of biodiversity.

Bog cotton © Fáilte Ireland

One of those is the Bog of Allen – a large raised bog in Ireland's Hidden Heartlands between the rivers Liffey and Shannon. There are many cut-away bogs here – where locals have cut turf to heat their homes.

The Bog of Allen Nature Centre is the place to get the lowdown on the history, culture and wildlife of the area. The woodland/peatland trails, gardens and exhibitions offer a comprehensive insight into the habitat and the people who have lived here for thousands of years.

A living nature reserve

The Irish Peatland Conservation Council, who manage the centre, also look after Lodge Bog, a living nature reserve with live sundews and curlews.

From the boardwalks, you can see how the tide of bog cotton has reclaimed the peatlands now that turf cutting has ceased here. Other flowers and plants also enjoy the serenity of the now blissfully quiet bogland: cranberry, bilberry, bitter vetch, bog asphodel. There is plant life here sufficient to bewitch the pickiest botanist.

Colm Malone, National Parks & Wildlife conservation ranger on Clara Bog, County Offaly

County Offaly’s Clara Bog, Ireland’s largest intact raised bog, is part of the Bog of Allen. Colm Malone, the local National Parks & Wildlife Conservation Ranger, probably knows it better than anyone.

“I’ve been working here since 1994 and am still entranced by it. In the spring and summer, a huge range of moths and butterflies are attracted by plant life.”

Look carefully and you’ll spot everything from the large heath butterfly, which lives nowhere else except on wet bogs, to the marsh fritillary.

Away from civilisation

“Basically, I fell in love with the bog. I love to be deep into the bog away from civilisation.”

Colm is attuned to the seasons turning.“A special moment for me is when the breeding curlews, the native birds, return in the spring. They seem excited to be back.”

Cycling at Lough Boora Discovery Park, County Offaly © Fáilte Ireland/Tourism Ireland

South of Clara Bog in County Offaly is the Lough Boora Discovery Park. On the Boora Bog, this area between the 1950s and the 1970s, supplied over a million tonnes of turf every year for commercial and domestic use.

This production has now ceased, and the land is being reclaimed for agriculture, eco-tourism and education. As well as its natural amenities Boora Bog is home to 24 splendid land sculptures, inspired by the area’s industrial heritage.

Stone Age discoveries

In 1977 a Stone Age site was discovered at Lough Boora. Excavations revealed a temporary settlement dated to the Mesolithic era, or around 8,000 years ago – stone axe heads, arrow heads, and blades were discovered, surrounding a series of fire sites. Our ancestors would have sat around the fire, doubtless spinning a few yarns about the day’s hunting.

Bog asphodel © Tina Claffey

Mongan Bog, also in County Offaly, is surrounded by classic raised bog countryside – a patchwork of pools, hummocks and flat “lawns” of sphagnum moss.

The hummocks are home to a wide variety of plant life, including ling heather, bog rosemary, cranberry, sundew and the sulphur-yellow, star-like flowers of the bog asphodel. Tina Claffey singles out the bogbean for special mention. “Its delicate yellow flowers are surrounded by white hairs – such a joy to see.”

Clonmacnoise, County Offaly © Fáilte Ireland/Tourism Ireland

Monasteries and castles

The Pilgrim’s Road to Clonmacnoise monastery settlement in County Offaly skirts the northerly edge of Mongan Bog before arriving at the monastery on the banks of the River Shannon. Just to the south stands Clonony Castle, built by the local MacCoghlan clan but subsequently seized by Henry VIII’s people.

It eventually ended up in Thomas Boleyn’s possession. Mary and Elizabeth Boleyn lived and died at Clonony, and would doubtless have wandered through the bogland perhaps contemplating the fate of their tragic sister, Anne Boleyn, executed by Henry VIII.

The sisters’ tombstone stands some 100 metres from the castle.

Clonony Castle, County Offaly

Less than 5km from Clonony lies the townland of Faddan More in County Tipperary. In 2006 Eddie Fogarty, working in the turf, uncovered a mediaeval psalm book.

It was open at Psalm 83, and Eddie became the first person in over 1,200 years to see the Latin words. But he didn’t delay long in going through the verses. He immediately covered the book with damp peat and got in touch with the National Museum.

Buried treasure

Eddie’s quick work helped preserve one of the greatest treasures from Ireland’s early mediaeval era. The psalter, probably written around 800AD, is now on show at the National Museum of Ireland. It would have been written at Clonmacnoise or any of a number of nearby monasteries.

The monks and scribes in the religious settlements of Ireland's Hidden Heartlands would have warmed their hands over turf fires. The great castles of the area too were kept warm by huge fires stoked with turf from the bogland.

Clonony Castle, County Offaly

Some 25km south of Clonony stands Leap Castle, reputedly the most haunted castle in Ireland. Owner Sean Ryan confirmed the former heating arrangements of this muscular fortress. “Turf yes, but with the environmental aspects of burning peat now clear, we’ve phased it out.”

Leap Castle has guarded the pass from Slieve Bloom into Munster since the 13th century. Uninvited guests – of whom there have been legions – were treated to boiling water, tar, arrows, rocks rained down on them from overhead murder-holes.

The castle is associated with many macabre legends. The Bloody Chapel gets its name from predictably gruesome goings-on in mediaeval times, but even now strange apparitions are noted – although thankfully of a more benign nature.

Leap Castle, County Offaly

L-R: views from Leap Castle; Sean Ryan, owner of Leap Castle; Leap Castle; the Bloody Chapel at Leap Castle

Sean Ryan and family have lived here since 1994. He takes the eerie aspect of Leap Castle in his stride and insists it isn't all doom and gloom. “Most of the spirits we see are good-natured, ” he says. “We've had no problems.

“But there's definitely a presence here. Some visitors find there's actually a physical barrier to entering. Some people have described a stranglehold round their neck.”

Who knows, spooky beings from the spirit world could well have emerged from Offaly’s bogs to do their haunting thing here.

From bog butter to oak roads

Nearby, in the townland of Glendossaun stands Clear Lake. Over 300 metres above sea level in the Slieve Bloom Mountains and surrounded by bogland, it never goes dry and it never overflows. But legend insists that it’s bottomless. So, mind how you go.

Clear Lake, County Offaly

Bog bodies, religious texts, tools, weapons and brooches from across the millennia have been found in the bog. Bog butter too: turf cutters in Ireland have often turned up chunks dating back as far as 5,000 years. Held in wooden containers or vessels, or wrapped in animal skins or bark, they beg the question – why did our ancestors want to bury butter?

Butter was evidently a valuable commodity, possibly used to pay taxes. So the bog was a handy “fridge”, or perhaps a safe place to hide it from thieves. On the other hand, the butter might have been a votive offering. Or, quite simply, burying butter in the bog might have improved the taste.

If you do come across some in the bog – best advice is, don’t spread it on your roll. Cover it in peat and call the museum.

Secrets of the bogs

L-R: Corlea Trackway, County Longford; bog butter at National Museum, Dublin © National Museum of Ireland; Hill of Uisneach, County Westmeath; boardwalk at Corlea Trackway Visitor Centre

Cuilcagh Boardwalk, County Fermanagh © Tourism Northern Ireland

Sphagnum moss, Clara Bog, County Offaly

A view of the Cooley Mountains and Carlingford Lough from the Flagstaff Viewpoint, County Down © Tourism Ireland

Ireland's blanket bogs

L-R: Roundstone Bog, County Galway; Céide Fields, County Mayo; Garron Plateau, County Antrim; Slieve Donard, County Down © Shutterstock