A taste of Irish whiskey

I’m sitting beside a giant gleaming copper still in a glass-walled still house, overlooking a small orchard and handsome manor house beyond, with two small servings of whiskey before me.

A whiff of one suggests wood smoke, turf fires and briny shores; a sip reveals subtle spice and peppery notes. The other? Caramel, honeycomb and dried fruit aromas, with a smooth mouthfeel that turns peppery behind sweet toffee notes.

We're in the Echlinville Distillery on the pretty Ards Peninsula just east of Belfast, at the “tippling” end of their Tour & Tipple experience. It has been as fun as it was enlightening, thanks to our guide Audrey’s cheeky quips and well-spun jokes.

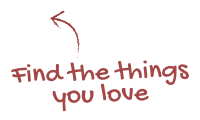

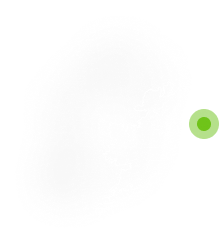

The manor house at the Echlinville Estate, County Down

There’s the one about the extra “e” for excellence in the spelling of Irish “whiskey”, to distinguish it from Scottish “whisky” – an old tease that is gaining new bite with the current boom in Irish whiskey – one of the fastest growing premium spirits in the world.

And there’s the story involving a local farmer who fertilises his pastures with this distillery’s abundant supply of boozy spent grain, leftover from brewing the wort (think low-alcohol sweet beer) to be distilled into new-make spirit.

This zero-waste solution works out very well for his happy pasture-fed cows, the farmer admits with a wink.

Tour guide Becky McKee, Tour and Tipple experience

Dunville's whiskey

For that new-make spirit to become Irish whiskey, Audrey tells us, it must spend at least three years and a day resting in barrels, though the longer the better.

It’s fascinating to compare this pair before me now, and how the different barrels used to finish the ageing of Dunville’s Three Crowns blended whiskey can layer such contrasting characteristics over those from the ex-Bourbon casks that the whiskey starts out in.

Barrels in the whiskey maturation warehouse at the Echlinville Distillery

Peated whiskeys are rare in Ireland. Audrey explains that those subtle smoky, briny notes in Three Crowns Peated are from a brief rest in second-use barrels purchased from across the water in western Scotland, where heavily peated Scotch is popular.

The sweeter notes of my second sample are down to final months spent in sherry barrels, a nod to Ireland’s long tradition of re-purposing sherry casks for its own whiskey production.

Becky McKee, the Echlinville Distillery

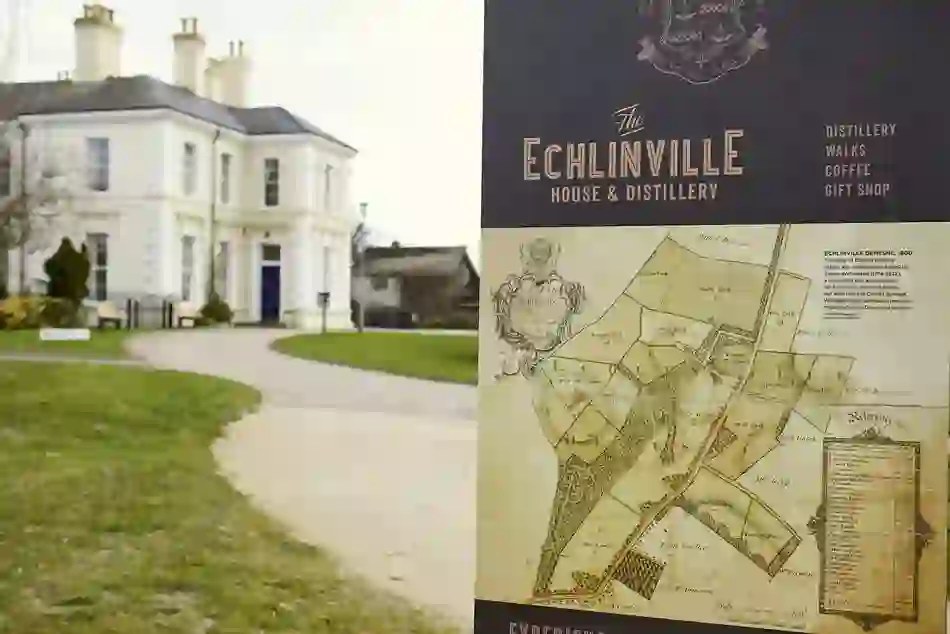

Bán Poitín

Some of my fellow tipplers are enjoying a neat nip of Bán Poitín, a clean earthy drop inspired by the un-casked Irish spirit that survived nearly four centuries of illicit production before its ban was revoked in the late 20th century.

Echlinville makes Bán Poitín for Bar 1661 in Dublin, which is leading a modern cocktail revival while also reclaiming the legacy of this most free-spirited of Irish beverages.

The Echlinville Distillery brands

Some others have opted for one of the four gins that this distillery makes – a number that reflects the parallel boom in Irish craft gins. There’s the light and lemony Feckin Gin, named after a local saint legendary for his magical powers.

There’s Jawbox, a small-batch dry gin scented with gorse flowers from the Black Mountains above Belfast; and crisp Weavers Gin, a tribute to the city’s historic linen industry.

Echlinville Gin is produced in the small-batch copper pot still that we can see on the still house floor below us, and flavoured with sweet sea kelp from nearby Strangford Lough, amongst other local botanicals.

The stables at the Echlinville Estate

The stables at the Echlinville Estate

Others, such as my gracious designated driver, are sensibly opting to redeem their drinks vouchers against a purchase from the well-stocked gift store. This is housed in the original outbuildings of what was once a 1,500-acre estate.

The nearby courtyard of the 17th century stables is earmarked for development into a museum celebrating the history of that estate and the heritage whiskey brands being revived here, including Old Comber, Matt D’Arcy and its flagship Dunville’s, which was one of Ireland’s most famous whiskeys before production paused in the 1930s for what turned out to be 80 long years.

The manor house at the Echlinville Estate, County Down

The manor house here was designed for the Echlin family by Sir Charles Lanyon, who left his mark on the Ulster landscape with constructions as varied as Belfast’s Custom House, Queen’s University, Crumlin Road Gaol and Courthouse, and the Antrim Coast Road with its Glendun Viaduct.

Now set on 18 acres, the property was bought by Shane Braniff, a fourth-generation Ards Peninsula farmer who moved to the estate with his wife Lynne and their three children in 2007.

Like many with an entrepreneurial streak and an eye on the Irish whiskey renaissance, Shane harboured a dream of making his own whiskey. By 2013 he had started construction on this ambitious still house.

The Echlinville Distillery, County Down

Three years later, the Echlinville Distillery made history as the first new distillery to open in Northern Ireland in 125 years. Several more have followed suit in what is a buoyant resurgence of Irish distilling across the island, with distilleries increasing tenfold in a dozen years from just four in 2010 to over forty and counting.

Distiller's Rest Cafê and the manor house at the Echlinville Estate, County Down

The Echlinville team are one of a few to pursue a field-to-glass vision. All barley for its new-make spirits is grown on the unspoilt peninsula, once the bread basket of Ulster thanks to its unique microclimate. Most of it comes from the Braniff family’s farms, where they also floor-malt barley by hand in the traditional fashion.

The tour with Audrey follows the journey of that barley from its arrival into two separate grain silos, for malted and unmalted barley respectively, to being weighed out in hoppers, milled into grist, moistened and heated in the mash tun to make the wort.

Grain silos at the Echlinville Distillery

Whiskey production at the Echlinville Distillery

We meet the small-batch copper pot still used to make Echlinville Gin, and the busy little experimental pot still used for product development. We file into the hush of a vast maturation house, where barrels of all shapes and sizes snooze their way towards whiskey excellence, with coded chalk writing giving hints as to the treasures within.

Audrey sprinkles this journey with juicy nuggets of history, such as why unmalted barley became key to Ireland’s traditional single pot still style. (Spoiler alert: 18th century Irish distillers embraced a high percentage of raw unmalted barley to counter crippling taxes on malted barley.)

Copper pot still at the Echlinville Distillery

Whiskey tasting at the Echlinville Distillery

The tour makes an excellent overview for newbies to Irish distilling but with plenty of insights for whiskey aficionados too. I learned for example that we have early 20th century American coopers to thank for today’s ready supply of second-use Bourbon barrels – their influential union lobbied for the existing law that specifies all Bourbon must be aged in new oak.

At the end of the tour, we take time to explore the estate’s grounds. There are plans to extend the visitor experiences here to highlight some excellent local food producers, and to pair Echlinville’s diverse drinks with the likes of Young Buck, a Stilton-style raw milk blue cheese made just up the road in Newtownards.

Exploring the grounds of the Echlinville Estate, County Down

You could happily make a day of it here on the Ards Peninsula by incorporating a few hours at the National Trust site of Mount Stewart, say, or an overnight of it to explore Strangford Lough by canoe with one of several local watersport companies.

For us, it was time to jump in our car as the sun set across the tidal lough, and follow the shoreside road back to the bright lights of Belfast city.

Strangford, County Down