Connect with the Celts

Blazing fires lit on hills in the dark of night, rituals to connect to the “Otherworld” and feasting on nuts and fruit – these are all ways the Celts celebrated Samhain – the ancient festival that Halloween derives from. Back then, it was one of the most important parts of the ancient calendar and heralded the start of winter.

“With Samhain, there’s the importance of the world around us dying,” explains Dr Kelly Fitzgerald, Head of UCD’s School of Irish, Celtic Studies and Folklore. “It’s a time to reflect on those who had passed before us.” It’s also a time when clocks go back and days get shorter, and as Fitzgerald notes, “Halloween is that time of year that we face our fears because we’re going into the darkness.”

Festivals were a way for the Celts to mark the year’s seasons. Alongside Samhain, they celebrated Imbolc in February as the entry to spring, welcomed the summer in May during Bealtaine, and marked the beginning of the harvest every August at Lughnasa.

It’s amazing to think that all these centuries later, we still celebrate Celtic festivals. But it’s not the only enduring connection to the Celts on the island of Ireland – from glittering jewellery to ancient forts, there are Celtic remnants everywhere, if you know where to look.

Tara Brooch

© National Museum of Ireland

The Celts arrived in Ireland around 500 BC, bringing their discovery of iron and knowledge of bronze and gold, leading them to design beautiful and intricate jewellery. At the National Museum of Ireland – Archeology in Dublin, you can view the stunning Broighter Collar, an Iron Age gold collar found in a hoard in 1896 near Lough Foyle in Northern Ireland, which has tiny bird and horse motifs on it. The influence of this intricate work was felt for centuries – the National Museum also houses the Tara Brooch, made around the late 7th or 8th century and inspired by Celtic designs.

In the Ulster Museum in Belfast, you’ll also find some Iron Age metalwork connected to the Celts such as the Bann disc. Decorated with Celtic designs, it’s a wonderful piece of jewellery from the era.

Celtic designs still inspire countless Irish jewellery makers today, so look out for the stunning creations from Brian de Staic, Tracey Gilbert and Fada.

Castlestrange Scribed Stone, County Roscommon

The Celts often used three-sided triskelion and spiral imagery, particularly a group of Celts in France who created what’s called La Tène art. You can find La Tène designs in Ireland also – just look at the Castlestrange stone near Athleague in County Roscommon, which is a large granite boulder decorated with spirals.

Over on Boa Island near Lower Lough Erne in County Fermanagh, there are incredible carved stone figures that are believed to represent pagan deities. Famed poet Seamus Heaney was so taken by one of them that he even wrote a poem about it, called January God.

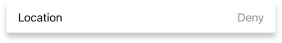

Dún Aonghasa, Inis Mór, County Galway

Promontory forts gave the Celts a great view of the landscape and helped protect them from nefarious invaders. One of the most stunning forts they’re connected to is Dún Aonghasa on Inis Mór, County Galway, perched on the edge of cliffs that plunge into the Atlantic Ocean.

Across the island in County Meath in Ireland’s Ancient East, there’s another important Celtic spot – Tlachtga or the Hill of Ward. Archaeological excavations suggest the hill was used for feasting and celebration over 2,000 years ago, and it’s believed the Celts lit a huge fire here during Samhain from which all the fires in Ireland were rekindled. Heritage tours of the hill are available as part of the Púca Halloween Festival.

In Armagh, you can visit the huge, 240-metre diameter Navan Fort, which is linked to the Celts through a temple built there in 95BC. This impressive site – which now has a visitor centre – is said to have been home to the Kings of Ulster. The Hill of the O’Neill in Dungannon, County Tyrone, is located on another ancient Celtic site linked to Geannan, who was once an important and powerful Celtic druid.

And of course, the Hill of Tara in the Boyne Valley, County Meath, is deeply connected to the Celts. It’s said to have been the dwelling place of the gods, as well as being the seat of the High Kings of Ireland.

Beaghmore Stone Circles, County Tyrone

There’s a huge amount of mythology dating from the time of the Celts, such as the story of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the mythical rulers of Ireland. They were said to have appeared out of dark clouds and landed on the slopes of County Leitrim’s Sliabh an Iarainn (“Mountain of Iron”).

Today, with three looped walks and a visitor centre at the site, Sliabh an Iarainn is a fantastic place to visit and marvel at the views and wildlife, from badgers to peregrine falcons.

In Cookstown in County Tyrone, you can take a walk to the intriguing – and possibly mystical – Beaghmore Stone Circles. While they date back to the Neolithic era, before the Celts arrived, there are marks on some stones that are thought to be Ogham, an ancient form of writing. It’s thought the Celts might have used the site for rituals.

While Knowth and Newgrange in County Meath were built long before the Celts travelled to Ireland, they were aware of and visited them. At Knowth, a number of bodies buried by the Celts were discovered along with grave goods, while you can also find Ogham written inside some of its passages.

Barmbrack

© Shutterstock

Because Samhain was a time when the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead grew thin, Celts are said to have disguised themselves in costumes to scare off ghosts and demons.

They would also use divination to predict the future, such as burning nuts to foretell if a couple were meant to be (if they burned together slowly, it boded well).

“When you think of all the games that are played at Halloween, a lot are about where you’re going with your life and what’s going to happen, and foretelling the future,” says Clodagh Doyle, Keeper at the Irish Folklife Division in the National Museum of Ireland.

A simple way to connect with this element of Celtic life today? Buy a loaf of barmbrack – and see if you’re lucky enough to find the ring.