St Brigid’s Day

She could turn water into beer and draw salt from a rock. Her prayers could stall the wind and rain. And when a man insulted her, she made his eyeballs implode.

I didn’t know she had such a temper. When I was a boy, I just knew her as nice, sweet Brigid of Brigid’s Cross fame – a four-pronged cross woven from straw, or rushes perhaps.

Nearly every house on the island of Ireland used to have them hanging above their doors and windows on St Brigid’s Day, 1 February, to keep fiery demons and other malevolent spirits away.

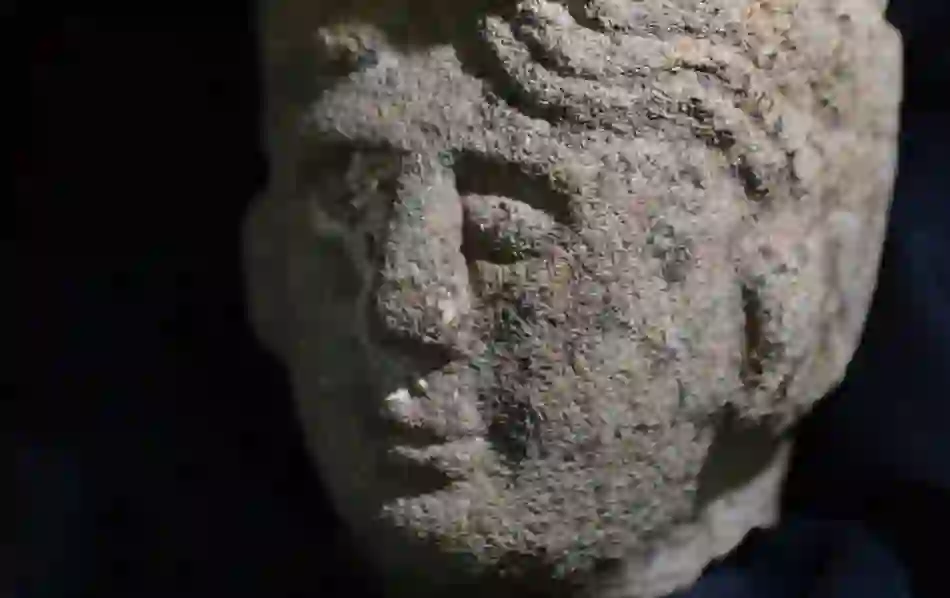

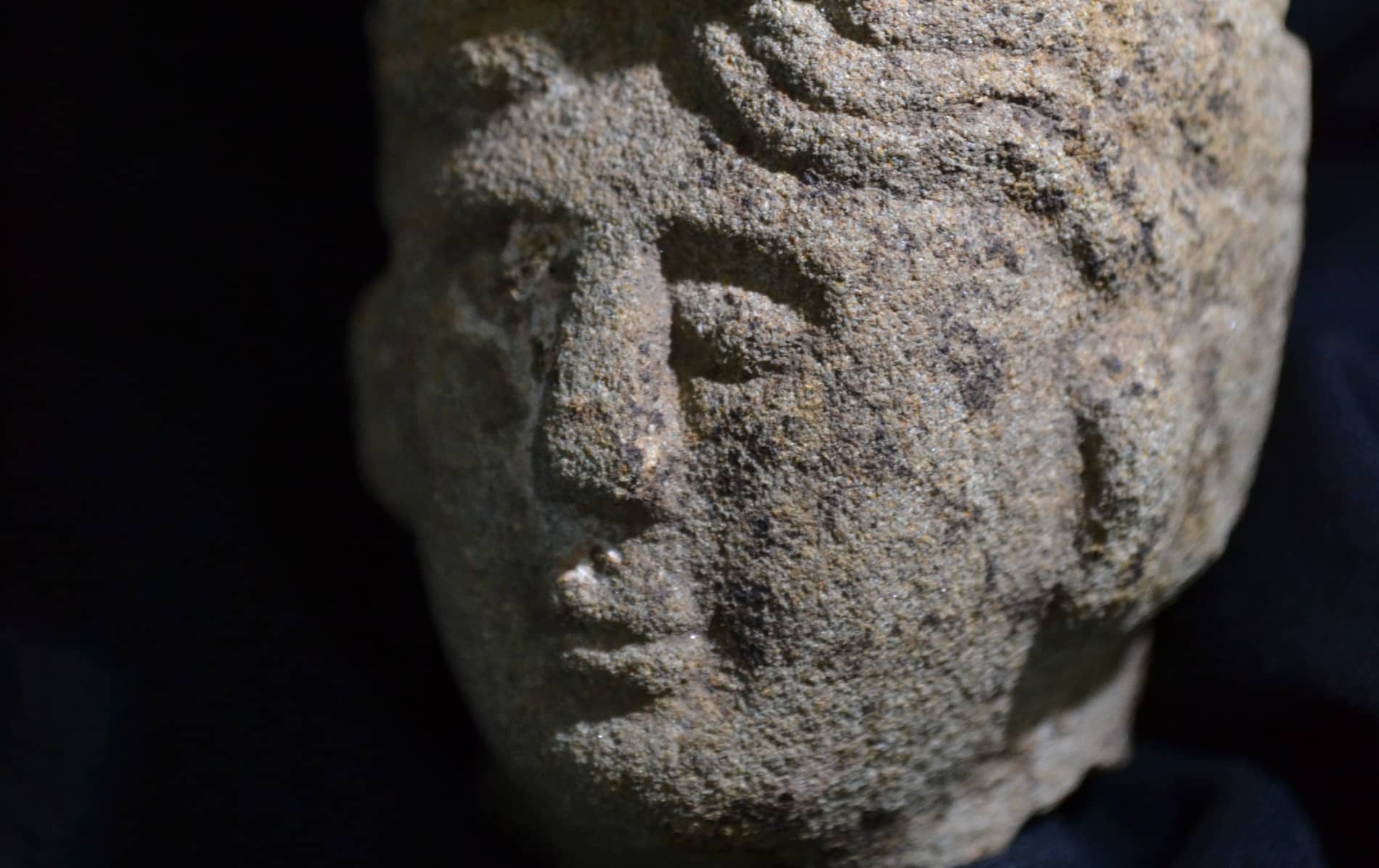

Statue of St Brigid, County Kildare

St Brigid was the protector. Over in the west of Ireland, girls wove Brídeóg dolls in her honour, while the young “Biddy Boys” would dress up and carry the Crios Bhríde (Brigid’s girdle) through the village.

The girdle was a giant ring of rushes. Hop through it and you were freshly blessed. Persuade the Biddy Boys to carry it through your house and stables, and you could rest assured that your family and livestock would be shielded against the darker forces.

Brigid herself would visit everyone’s house on St Brigid’s Eve, so you were supposed to make up a bed and leave some food and drink out for her, just like you leave milk, biscuits and carrots for Santa Claus and his reindeer on Christmas Eve. You might even put a cloth or a scarf outside for her to bless as she passed; the Bratog Bhríde (St Brigid’s mantle), as it was called.

St Brigid's Shrine, Faughart, County Louth

Myths and miracles

There were plenty of tales told of St Brigid. Her father was a chief, her mother a slave, and Brigid was born in about 450AD, just as the Roman Empire was collapsing, and about two decades after St Patrick began his grand tour of Ireland, converting the pagan chieftains to the Christian faith.

From her upbringing on a family farm in Faughart, County Louth, she grew into a young woman “dedicated to goodness”. She strolled the countryside, milking cattle, feeding the hungry, healing the sick. So pure was her soul that flowers and shamrocks sprang up wherever she walked.

And the miracles? Brigid just knocked it out of the park when it came to miracles. She racked up 46 of them, according to one of her very first biographers, narrowly trumping Jesus himself.

She made her debut in her early teens when she gave all her precious milk and butter away “to the poor and to wayfarers”, only to have her supplies wondrously replenished that very night after she “turned to God in prayer”.

St Brigid around Ireland

L-R: St Brigid’s Cathedral, Kildare town; St Brigid’s Well, County Louth; illustration of St Brigid; Hill of Uisneach, County Westmeath

Brigid and the King of Leinster

Most of St Brigid’s miracles involved animals – curing them, rescuing them, saving them from nasty humans. She also earned a hallowed place among the patron saints of beer after she somehow squeezed enough beer out of a single barrel to satiate the parishioners of 18 different churches.

The beer trick was impressive. However, her standout miracle was the one she achieved when she asked the King of Leinster for some land for her fledgling community in Kildare. To backtrack a little, on the eve of womanhood, Brigid rejected a marriage proposal in favour of life as “a chaste virgin to God”. She was duly “veiled” as a nun at Croghan Hill in County Offaly, or the Hill of Uisneach, or Fartullagh, both in County Westmeath, depending on which version of events you read.

According to one rather cool account, she then set off by chariot on a mission to spread the faith around the Kingdom of Tethbae, now counties Westmeath and Longford.

The Curragh, County Kildare

Land for her church

One way or another, Brigid fetched up on a grassy ridge on the western edge of the gorse-covered Curragh plains, along with a bevy of other nuns, of whom she was very much the leader.

They were clearly a very capable lot as they then constructed a small church of oak on that ridge. The Irish word for church is “cill” and the old Irish word for oakwood is “daire”. Put the two words together and, over time, you get Cill Dara, or Kildare, from which the entire county takes its name.

A church is all very well, but Brigid needed land to go with it. So she met with the King of Leinster who tells her she can have as much land as the cloak on her back can cover. Next thing, Brigid has whooshed out her cloak, handed a corner each to four holy maidens and instructed them to sprint in four directions as far as they can.

It turned out to be a most magical cloak, spreading far and wide across Leinster. And so it was that the king awarded Brigid’s new church a huge estate, including the fertile Curragh grasslands, on which her sheep and cattle could henceforth graze.

Scenes from Kildare town

L-R: St Brigid’s Cathedral; St Brigid’s flame; Firecastle Café; statue of St Brigid

Putting Kildare on the map

A monk who visited Kildare in the 7th century described Brigid’s original church as being “of awesome height towering upwards … adorned with painted pictures.” That wooden church propelled her to stardom as one of Ireland’s three national saints, while Kildare itself was among the most important early Christian foundations in Ireland.

According to one early visitor, it was “a vast metropolitan city and the safest city of refuge in the whole land of the Irish for all fugitives, and the treasures of kings are kept there.”

Fast forward 1,500 years and Kildare continues to be St Brigid’s bastion. Located 50km southwest of Dublin, this lively, friendly, vibrant town is replete with restaurants, gastro pubs, bistro cafés, grocers and pubs.

A weekend food market blossoms on the newly pedestrianised town square, which slopes down the original ridge of Kildare, with stalls springing up between oak trees and potted plants. Peaceful tunes drift out from the Firecastle café, accompanying the aromas of sourdough. And there’s a clear sense of Kildare’s sporting tradition in horse-racing, rugby and Gaelic football.

In the centre of the square, the heritage centre invites passers-by to enjoy “Legends of Kildare”, a virtual reality tour of the town’s history in which you meet Brigid the Goddess and St Brigid, as well as other characters from Ireland’s Celtic mythology and medieval past. The entire show takes about 30 minutes and is an excellent way to wrap your head around such events.

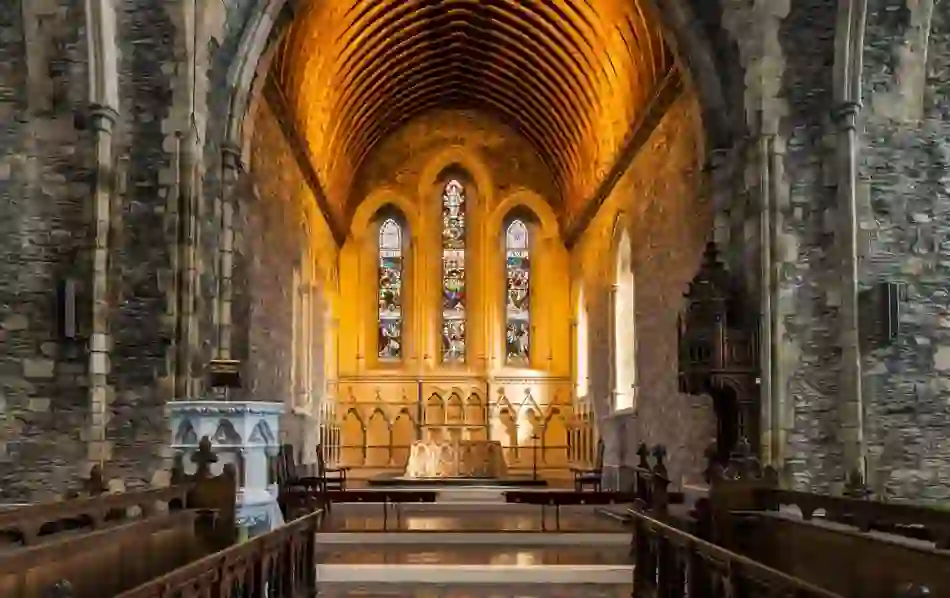

St Brigid's Cathedral, Kildare town

A favourite of the Vikings

On the hour, the bells ring out from sturdy St Brigid’s Cathedral, built on the very spot where our eponymous heroine constructed her timber church. Surrounded by a high stone wall, the cathedral complex includes part of a high cross and a soaring round tower built in an age when the Vikings were on the rampage. They targeted St Brigid’s Cathedral sixteen times between 835 and 998.

Also within the cathedral complex are the remnants of the Firehouse where a perpetual fire burned in memory of “the glorious Brigit”. In the 12th century, the Cambro-Norman chronicler named Giraldus Cambrensis described how this flame was tended by 19 nuns. Surrounded by a circular hedge, this was very much women-only territory. Should any “rash” man try and enter, Giraldus warned, “he will not escape the divine vengeance.”

A medieval archer who leapt over the hedge and blew upon the fire lost his mind and drowned himself. Another invader found “his leg and foot instantly withered”.

Solas Bhríde, Kildare town

A lasting legacy

Alas, such threats didn’t stop the spoilsports of the Reformation from extinguishing the fire when they smashed St Brigid’s historic abbey to smithereens in the 1530s.

Happily, the Brigidine Sisters came to the rescue and gamely ignited a new perpetual flame at an Afri justice, peace and human rights conference in 1993. (The Brigidines are, as the name implies, an order of nuns dedicated to St Brigid.)

You’ll find this gentle flame burning in a beautiful bog oak sculpture at the Solas Bhríde Centre and Hermitages just outside Kildare town, near the Tully holy well.

As Brigidine Sister Phil O’Shea explains: “We keep it burning as a beacon of hope, justice and peace for our world. It has caught the imagination of so many people. They all find different things in the flame. Some are from the goddess tradition, some come from the saint where it is symbolic of the light of Christ.”

Solas Bhríde, Kildare town

The Solas Bhríde centre opened in 2015 and takes the shape of a Brigid’s cross. Sister Phil, who co-founded the centre, believes the saint herself is growing in contemporary relevance.

“Our centre looks at the legends of the saint and how they speak to us today. A lot of her stories are about her care of the earth and the land, for our climate. She also sought justice for the poor, which very much resonates today.

“She was renowned as a peacemaker, as a woman of hospitality and as a woman of deep contemplation. There is always some part of her that speaks to us.”

The pagan back story

A flame from the Solas Bhríde fire lights the fire that burns in Kildare town for the duration of the St Brigid’s Festival each year.

Now, this perpetual flame does kind of light up the elephant in the corner with this tale. Fires, especially eternal ones, are very much part of the Christian thing but there’s also something kind of pre-Christian about it all. One thinks of the vestal virgins who tended to the sacred fire at the temple of the Roman goddess Vesta.

Bottom line, St Brigid has a mega back story. Of a kind that means nearly everything you’ve read in this article up until this point starts to go a little wobbly. Because it turns out that St Brigid has an awful lot in common with a few pre-Christian pagan goddesses.

Statue of goddess Bríg

First up is Bríg, a mother Celtic goddess of the mythical Tuatha Dé Danann, who was nourished on sacred cow’s milk as a child. Sound familiar? Her husband ruled as king of Ireland for seven lousy years until he was poisoned. Although one version says he actually abdicated and became an agricultural consultant.

To further complicate matters, the pagans also worshipped a triple deity, comprising three sisters, all called Brigid, dedicated to poetry, healing and smithcraft respectively. Then we have those who believe that both Brigid and Bríg are extensions of a dawn goddess venerated by Indo-Europeans since the deep, deep past.

Throw in the proposition that she’s a variation of Brigantia, the Celtic equivalent of the Greek goddess Athena or of the Roman Minerva, and one’s pupils are likely to start dilating.

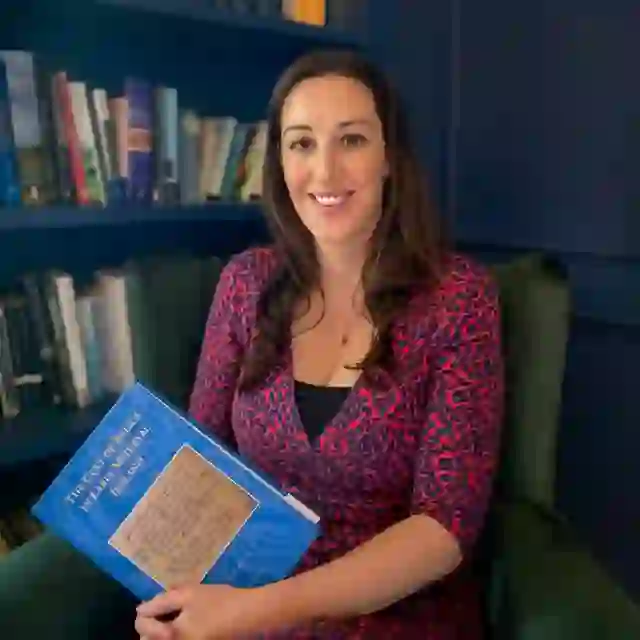

Dr Niamh Wycherley, Department of Early Irish, Maynooth University

St Brigid’s story

I sought help from Dr Niamh Wycherley of the Department of Early Irish in Maynooth University. She’s also the author of The Cult of Relics in Early Medieval Ireland, winner of the NUI Publication Prize in Irish History 2017.

“There is no one true Brigid,” says Niamh. “No clear factual narrative about her exists. People have been rebranding and reinventing her for at least 1500 years. Her story has been moulded by communities in various places for different reasons. Both the goddess and the saint encapsulate stories made up by later generations.”

St Brigid’s Holy Well, County Kildare

Even St Brigid’s most ardent Christian fans concede that the facts are somewhat fluffy. Trying to untangle the myths and truths is a puzzle for the ages, riddled with rabbit holes. Imagine someone a thousand years from now trying to make sense of our present age by reading a book about Spiderman and Luke Skywalker.

As Niamh observes, we shouldn’t lose track of the fact that there was a woman, probably called Brigid, who established Kildare as one of Ireland’s holy hot spots.

“The real Brigid who founded Kildare should be applauded for making such a huge mark in a man’s world,” says Niamh. “For centuries afterwards, the Abbess of Kildare was arguably the most powerful woman in Ireland.”

Old Faughart Graveyard, County Louth

21st century feminist icon

Her commanding role as Abbess of Kildare in a world dominated by men also explains her position as a feminist icon in the 21st century. When the Church of Ireland appointed Patricia Storey its first female bishop in 2013, she was given the united Dioceses of Meath and Kildare.

In time, St Brigid herself would become “Muire na nGael” (Mary of the Irish), as venerable as the Blessed Virgin, mother of Christ, and second only to St Patrick in the hierarchy of patron saints.

Kildare boomed on the back of her success. Pilgrims came to marvel at her tomb, “adorned with a refined profusion of gold, silver, gems and precious stones with gold and silver chandeliers hanging from above.”

The cathedral city evolved into a major centre of theology and learning, complete with an oratory, a scriptorium and a school of art where metalwork and illumination were taught.

Those pilgrims would also bring the stories of St Brigid to Britain and the European continent, and she thus became an international saint, revered in cities such as Cologne and Lisbon.

Celebrating spring

L-R: Daffodils in bloom; a lamb and ewe on The Curragh; an offering at St Brigid’s Holy Well; spring flowers in the countryside

Brigid and the start of spring

Aside from being a woman, the other thing that all these Brígs and Brigids have in common is that their feast day comes right at the start of spring. St Brigid’s Feast Day (Lá Fhéile Bríde) falls on 1 February, the date on which she apparently died. As of 2023, this became a new public holiday for Ireland, a joint celebration of St Brigid’s Day and Imbolc.

Imbolc is one of four Quarter Days celebrated in pre-Christian Ireland. Pitched midway between the winter solstice and the spring equinox, Imbolc translates as “the belly” and refers to ewes on the cusp of lambing.

For an agricultural society, it was an immensely significant time, marking the transition from winter to spring, the first bleats of new-born lambs, a new lactation cycle for cattle. As such, 1 February was celebrated with a festival replete with St Brigid’s symbols, including fertility and propagation.

That celebration continued when the Christian church began to celebrate St Brigid’s Feast on the same day as Imbolc. If you’re in Ireland next 1 February, head for one of the hundreds of St Brigid’s Wells across Ireland.

Quiet contemplation at St Brigid’s Holy Well, County Kildare

Aside from St Patrick, St Brigid has more wells dedicated to her than any other saint. In fact, she actually beats St Patrick in counties Kildare, Dublin and Laois and even in the distant kingdom of Kerry, she has 11 holy wells, making her the third most popular saint in that faraway county.

Some of the wells dedicated to her are, inevitably, also associated with the goddess Bríg.

St Brigid’s wells around Kildare and Louth

L-R: St Brigid’s Holy Well, County Kildare; St Brigid’s Cross, County Kildare; Brigid’s Wayside Well, County Kildare; St Brigid’s Shrine, County Louth

Sacred wells and cure-alls

In centuries past, people gathered by these sacred wells on her feast day every year. Many were renowned for curing poor eyesight; others helped induce pregnancy and eased labour pains. Still more were for infertility and impotence.

Such wells are often accompanied by a “clooty” tree, predominantly a hawthorn, bedecked with ribbons, bandages and others curious trinkets left as offerings from the people to the saint or goddess, take your pick.

“Clooty” tree at St Brigid’s Holy Well, County Kildare

There are two fine wells at Tully, just outside Kildare town. The first is the Wayside Well in the carpark of the Irish National Stud and Gardens. The second is the nearby Tobair Bride (St Brigid’s Well) where a clear, shallow stream serenely flows through a lightly landscaped grassland with a stone shrine and the holy well itself. There were at least five trees around it covered in offerings – rosettes, necklaces, ribbons, tricolours, Brigid’s crosses.

On my visit, an elderly lady from Sligo was there with her nephew and niece. As we made small talk, the nephew rather humbly asked if I would mind if he tied a face mask to one of the branches. Their uncle was in hospital with Covid, and they hoped this would help. It was astonishing to see this ancient folk tradition in such a current light.

St Brigid’s Shrine, County Louth

A Brigid for everyone

As Sister Phil says, the beauty of Brigid is you can kind of choose the version that suits you. Maybe you like her kindness to animals or her generosity to the poor. Or how she befriended lepers and helped the mute speak. Or her reputation for making exceedingly good blueberry jam.

Her story has been consistently reimagined and revamped by each new generation. Fifty or 60 generations after her purported life, she remains one of Ireland’s most popular saints, the champion of the downtrodden, the religious lynchpin of innumerable communities.

As a patron saint of babies, midwives, cattle, computers, blacksmiths, beer and numerous other duties besides, it is quite clear this saint has no intention of vanishing from the contemporary world.

Her determination to stamp out evil resonates strongly today, as does the manner in which she overcame the adversity of her birthright to become such a powerful force of goodwill.

St Brigid’s Cross, St Brigid’s Shrine, County Louth

What’s in a name?

The old Irish word “Brigit”, from which we get “Brígid”, is said to derive from “brígh”, meaning a “strong and protective woman”, or from “brigantī”, meaning the “high” or “exalted one”. Its most popular form is Bridget.

Look up Bridget on the 1901 census and you’ll find 154,000 Irish women who would have responded to that name. That’s before you run with the multiple spellings (Bríghid, Briget, Bridgette etc.) and variations (try Brid, Bridie, Bride, Biddy, Bridge, Bridgie, Breda and Breeda).

Some variations fared better than others. Biddy’s popularity waned when it became a pejorative slang term for a fussy, old woman. Similarly, “Bridgets” became a somewhat derogatory term for Irish women working as domestic servants in the US during the 19th century.

Prior to 1965, all girls in the Catholic diocese of Kildare and Leighlin were required to take Brigid as their confirmation name. If they were already named Brigid, they would take Mary.

In Ireland, there are at least 62 townlands and 18 parishes directly connected to St Brigid. As well as the holy wells, she has scores of churches, schools, convents, GAA clubs and hospitals dedicated to her in Ireland.

Indeed, her cult is to be found in every corner of the world from Australia to Vermont. She even has an ice-covered island named for her in Antarctica.

Looking for Brigid around the island

L-R: Brigid of Faughart mural, Dundalk, County Louth; St Brigid’s Cathedral, County Kildare; Brigit’s Garden, County Galway; Solas Bhríde, County Kildare

Seven places to discover Brigid

St Brigid’s Cathedral, Kildare, County Kildare

The town of Kildare hosts an annual St Brigid’s Festival (Féile Bríde), part of which takes place at St Brigid’s Cathedral. Built on the site of the original church, it was effectively a ruin by the time Cromwell’s army reached Ireland in the 1640s. Partly reconstructed in 1686, it sank back into the mire again before it was completely rebuilt between 1875 and 1896. A highlight is the Fire Temple where the perpetual flame was once held.

Solas Bhríde Centre & Hermitages, Tully Road, Kildare town

A Christian Spirituality Centre, where the Brigid Flame, re-lit in 1993, burns as a beacon of hope, justice and peace for the world.

Brigit’s Garden, Roscahill, County Galway

A beauty at the gateway to Connemara, with four gardens that each represent one of the Celtic quarter festivals of Samhain, Imbolc, Bealtaine and Lughnasa.

Brigid of Faughart Festival, Hill of Faughart, County Louth

Taking place on a modest but deeply historical hill near the Northern Ireland border, the festival offers “different ways through which the wisdom of Brigid can be accessed,” both as a pre-Christian goddess and as a Christian saint. It also explores her relevance to contemporary society through Irish mythology, landscape, folklore, spiritual customs, pilgrimage, poetry, music and dance.

Delany School, Tullow, County Carlow

Bishop Daniel Delany founded the Brigidine and Patrician teaching congregations in Tullow in 1807 and 1808 respectively. The fine Bishop Daniel Delany Museum in the Brigidine Convent gives a history of these orders and displays artefacts associated with the bishop. The museum may be visited on appointment by contacting Tullow Parish Centre, telephone 059 91 51277.

Brigid – Spirit of Kildare, County Kildare

This vibrant festival celebrates the life and legacy of St Brigid with a rich offering of concerts, workshops, talks and much more, all led by local communities and artists.

Brigit: Dublin City Celebrating Women, Dublin

From embroidery workshops and live music gigs to cleansing ceremonies and the Imbolc Fair, over 80 exciting events will take place across the city, showcasing the women shaping our world today.